texas at 10 (9-15-2013)

Ten years ago today, my first album, texas, was officially released.

Wow.

In some ways,

that doesn’t feel possible. A decade seems like a long time. But

then, when I stop to consider whether the person who made that album and

the person speaking to you now are one and the same, it really does feel

like a very long time ago. A lot of things have happened to this mind

and this body since that period, and that record is, as it was meant to

be, a document of a moment in time.

Why do I consider this milestone to be worthy of an essay? Partly I am

driven by my inner historian, eager to compare and contrast the old with

the new (and of course to re-contrast at 20, etc). But the reason I’m

doing this out loud instead of to myself is in large part because over

the past ten years, so many people have personally professed to me such

warm feelings about this album that I feel I owe it as much to them as

to anyone else to set down an account of its creation.

From an outsider’s perspective, texas seems like a beginning.

But at its genesis, that record was as much about where I had already

been as about where I was going.

1999 was an important year for me. That February, my band The Civilians

released a 4-song EP, the first CD offering any band of mine had ever

managed to produce. We had spent bucketloads of dollars and months of

finagled studio time to get it right, and with a packed release party

at the Flying Saucer in Fort Worth, it briefly felt like a triumph.

But within days, there came a creeping realization that the record was,

at best, mediocre, both sonically and musically. It was hard to take,

after so much work and sacrifice, to see something so lifeless as the

ultimate result. The fact frustrated me, but I largely kept my opinion

to myself. After all, we had truly done the best we could. That frustrated

me as well.

Not two months later, I got laid off at my crummy data entry job. This

went down merely a week before my wife and I were to get on a plane to

the UK for our 1-year wedding anniversary vacation. With that bit of uncertainty

(and a slight impact on our trip budget), we disappeared into another

country for two weeks. It was the longest time I had spent away from music-making

since I’d first started in my teens.

The absence of that constant tugging from this-must-be-done and that-must-be-done

was both calming and unnerving to me. Music was the life I chose; why

was I relieved to be away from it? I stowed that thought away as we returned,

for there were bigger fish to fry, and a landlord to pay.

Almost upon walking in the door, I pulled out my rolodex (yes, a real

rolodex) and called everyone I knew, placing particular emphasis on contacts

I’d gotten during my days booking music at Borders. One of them,

the inimitable Little Jack Melody, called me back, and within a week,

I had a job.

There may be a book waiting to be written about the experience that was

w3cd.com. It was an online music store, but for me, it was infinitely

more. The staff was made up almost entirely of Dallas music scene veterans,

many of whom had been signed to majors before a wave of corporate mergers

had zeroed them out of their contracts. These were people who knew about

music from the corner bar to the limo to the broken promise, and there

we all were, shoulder to shoulder in the retail trenches every day. I

could not have asked for a better place to be at that time.

Weakly, I distributed copies of my band’s EP among them, but of

course they all had far more impressive offerings from their back catalogs.

However, it was then that I became aware of a fact that would transform

my entire outlook from that point forward. In the process of passing music

around, I discovered that one of my co-workers, Casey Hess, had recently

put out a fairly successful album (Jump Rope Girls, 8 Track Demos)

that he had recorded mostly on his own at home with an 8-track digital

recorder. I was flabbergasted by how much better it sounded than the pitiful

EP we’d spent so much money slagging out in a legit-looking studio.

What was more, another co-worker, Talley Summerlin, showed me some demos

his band BE were making on their home recording unit (a set of songs which

became the beautiful Thistupidream album). Again, I was flummoxed

by the quality. Here were two people, earning the same wage as I was,

creating sounds far beyond what I could with my best efforts and precious

investment.

Coincidentally, certain heroes of mine were also making the jump to independence.

Glen Phillips, in the wake of Toad the Wet Sprocket’s breakup, made

a self-financed solo album. Aimee Mann bought her masters from the label

and put out Bachelor No. 2 by herself. I had seen local hero

Sara Hickman do the same a few years prior, and the idea seemed to be

spreading.

It was about this time that mp3.com and Napster emerged from the froth

of the internet, sending shock waves through the music industry. I took

a hard look around me. It became more and more evident that I needed to

revise my assumptions about how to conduct a career in music. I hit the

bulletin boards, and picked the brains of my compatriots till they were

sore. With every sports bar gig and lukewarm review, I began to think

about exactly who I was and what precisely I wanted to do. I tossed out

the old plans, and made new ones.

In January of 2000, a few days after my 26th birthday, I played my last

gig with The Civilians. Ironically, I put more into that performance than

I had in years, so much so that it almost made me question my departure.

But the sensation driving me that night was freedom. From expectations,

from band politics, from creative restraint, from damned near everything,

so it seemed. I didn’t even know what I was going to do, but I knew

it would be something different.

The very next week, I bought a used Roland VS-880 digital recorder on

eBay. All through 2000 and 2001, I spent nearly every free moment in our

spare bedroom tinkering with that thing. Sometimes it was as simple as

sticking a microphone out the back window and seeing what happened. Occasionally

I would take it out on the back porch, press record and just talk &

play guitar while it ran. If a song happened by, I’d take it into

the studio and monkey with it.

A bit of time was spent going through half-finished lyrics and riffs from

the rock band years. These provided the basis of tunes like Bring

Me Safely Down, Old Enough (the only Civilians tune to survive),

Mountaintop 4th of July, Union Station, and the Theme

from texas. I found the lyrics for Office Suite, Part I in

a diary I’d kept on the train, and put them to music. When that

worked, I put down a music bed for the rant that became Part II.

I tried a few covers. The Roof Is Leaking was the only one to

make the cut, but several others nearly did (Mull of Kintyre

and Fat Old Sun coming very close). My old Average Deep and Civilians

partner Jeff Simms was kind enough to lay down some drums & backing

vocals where I needed them, despite me pulling his band out from under

him.

I played no gigs. I visited no open mics. I barely attended any shows.

When w3cd came crashing down with the rest of the dot-coms in October

2000, my contact with the outside music world diminished. I spent my clerical

dayjob hours thinking of things to do in the studio, and tried them out

when I came home. I followed ideas down rabbit holes until they either

turned into something concrete or crumbled like spent matches. I knew

that eventually, there would probably be enough material for an album,

but I had no timetable on when that was going to be, or what it was ultimately

going to sound like. Me being me, there was a certain level of anxiety

about productivity, but nothing on the scale I had experienced in a musical

democracy (even though most of that was under my own whip).

Listening back now, of course, I hear all the misplaced microphones, bad

edits, and the omnipresent deviated septum which would require surgery

only a few years later. But I’m not the only one who hears something

else. It’s the sound of fun, of unbridled experimentation. I did

things just to do them, because I could. I played the inside of my van

with a set of car keys. I left cables unplugged to get static hum. I ran

things through cheap pedals long discarded, in search of a sound that

might unlock another idea. Anything was possible, because why the hell

not?

I think this accounts for why so many of the people who want to talk to

me about this album are musicians. There are so many good musicians who

feel as if they’re wearing ankle chains tying them to so many things:

Their band members, the scene, clubs, what have you. Somehow they can

hear those things being cast off on that record.

I would occasionally share rough mixes with the aforementioned Mr. Melody,

and he gave me a very valuable piece of advice from his own experience

as a solo artist breaking free from a band: Take your chances now, because

everything you do afterwards will be put up against this baseline. No

one knows what you can or can’t do yet. Throw everything you’ve

got at ‘em. There is absolutely nothing to lose.

I kept these words in mind during deliberations on whether I should include

novelty-style tunes like the two Office Suites. Sometimes they

felt too gimmicky to me, and I couldn’t see them fitting with the

more sweeping material. Indeed, the official criticism upon the album’s

release was almost invariably that I should have scrapped either the ballads

or the jokey songs and made it all sound more unified. But hearing from

those who hold it dear, this contrast is essential to its charm.

In the fog of creation, I gave the matter of reviewability no attention

whatsoever. This thing that I was doing was in direct opposition to the

music industry, and the less I concerned myself with their potential opinions,

the better. I barely spoke to anyone in that world by then, anyway.

Of course, the rest of my life was hardly standing still while I worked

in my little room. Indeed, the dissatisfaction I felt with the music industry

was only part of a larger discomfort my wife and I were feeling about

the place we found ourselves in as we approached our thirties. I do think

that my tossing out the connection to the local scene helped us to feel

more confident in leaving the only state we’d ever known and trying

to make a go of it in New York City.

My good friend Thomas Spencer put us up in his spare room for the last

half of 2001 so we could save money for the move, and it was there that

I began the process of separating real songs from half-formed ideas. There

were some items still on the borderline, but a definite stack of castoffs

was put on the spike, and I spent more time honing the keepers and maybe-keepers.

It was beginning to sound like something. It didn’t sound like anything

I’d ever done before, and I liked that. The trusted ears I showed

rough mixes to could hear the shaky bits here & there, but they all

agreed that I was on to something, whatever it was.

The plan was for my wife to move to NYC in February and get us established.

I would stay in my old room at my parents’ house until June, finishing

the parts of the record that needed to be done in Texas, then following

her up north.

This mostly worked. Mostly.

I did indeed spent a few weeks in Weatherford, calling in all my favors.

Little Jack played for me, and hooked me up with his keyboardist Brad

Williams, and with the great Reggie Rueffer to do violin tracking. My

old friend Nancy Giammarco, whose band Blanche Fury had played with my

bands so many times in the ‘90s, came by to add backing vocals.

Knowing that I was headed to a shoebox apartment in the city, I recorded

all the loud guitar bits I needed in my old bedroom, likely adding some

stress to the early stages of my father’s retirement. I got the

album as ready as I could.

Then the damned radiator went out on our car, and the jig was up. The

timetable got clipped, hard. I packed up my music & recording gear

in a box, indefinitely, and made haste for NYC at the beginning of May

2002.

It sounds odd to say, but in the first few months of my NYC experience,

music was pretty much the last thing on my mind. The rubble piles from

the 9/11 attacks were still fresh, and a lot of things were upside-down,

both in the lives of two Texan transplants and in the culture at large.

My typing speed and clerical experience yielded me many disparate temp

jobs, and with New York prices, all our cost-of-living expectations had

to be recalibrated. It was choppy there for a while.

This was the period in which I started writing the Letter

From NYC, a fairly popular item that got forwarded around and helped

build an audience for the launch of thematthewshow.com, which debuted

in October 2002. Writing for that site helped occupy my creative energies

until I could return them to music.

By late ’02, we were confident enough in our residency that I sent

for my VS-880. Upon its arrival, my heart nearly stopped. Someone had

handled it roughly. Its 8 track capacity had been knocked down to 7, and

the best damned song on the record, Bring Me Safely Down, was

corrupted. Jeff’s drums. Reggie’s violin. Nancy’s vocal.

Gone. Only a rough cassette copy of the mix survived, patchy and forlorn.

I was stunned. Dumbstruck. How? Why? WTF? HTF? MF?

BUT…

Perhaps it was the fact that my job at that time was located right next

to two blasted craters of twisted metal. Maybe because we had moved to

that city mere months after the largest attack on American soil since

WWII and had managed not to come running back to Texas with our tails

between our legs. I can’t say for sure.

In any case, I decided very firmly that this was NOT the end of this album.

I had worked too hard, come too far. Not just since 2000, but since 1991.

This was me kicking off the shackles, and by damn, they were coming off

one way or another. I needed a workaround. I had to find some local help.

And look where I was, for chrissakes.

The murky hand of fate was very busy on Craigslist at that time. There

I found a pianist who told me he’d be playing at a bar on the Upper

East Side one night. It was out of my way, and past my bedtime, but I

went anyway. Arriving on time, I found an empty piano bench and a mostly

empty bar. Assuming the guy would get there at some point, I ordered a

drink and vainly tried to people-watch.

The bartender was unusually loquacious, and a musician himself. I’d

spotted him at fifty paces, but New York’s full of ‘em. Having

sampled a few crappy open mics in town, I was guarded about outing myself

before I knew who I was dealing with. However, then he began quoting Bill

Hicks. This, for your reference, is a surefire way to grab my attention.

Turned out the man was not only a pianist, but a producer and songwriter.

His name was Paul Shapera, and were it not for him, texas would

not be the album it became.

We met up a few days later, and I showed him where the holes were in my

musical wreckage. He had ideas for what to fill them with, plus patches

for spots I hadn’t even thought of. From the embers, the beast was

being slowly resurrected. Paul put drums, bass, and keyboards where they

needed to be, and the flesh returned to the bones.

There were, of course, things that could only be had in Texas. I was totally

married to Reggie & Nancy’s parts on Bring Me Safely Down,

and when the opportunity came to fly down for a visit, I re-recorded them

almost exactly as they had been on the original recording. Learning my

lesson from the previous catastrophe, I made about eleven backups of the

sessions, leaving several scattered with friends around DFW, before returning.

By early 2003, it was down to the nut-cutting. This was certainly an album,

and it needed to be set free. Something was bothering me, though, and

I didn’t know if it should. It seemed to be one ballad too heavy.

The uncertainty came from the fact that my favorite album in the world

is The Final Cut by Pink Floyd, which is about 90% ballads. But

it was very clear by now that this was not the same sort of album at all.

This had fun things in with the ponderous ones, and was riddled with jangly

stuff from the R.E.M./Toad school as much as from the classic rock pantheon.

Unbidden, my good friend Jason Jackson called me from Texas and pissed

me off with one thing or another, and from my guitar sprang a bouncy,

angry tune; the first I had written in New York. Thus was born The

Loneliest Boy In Toyland. I made a demo and brought it to Paul, who

proceeded to lay down a bed of wonky drum machine sounds for me to scatter

guitars around on. It was exactly what the record needed. I tossed one

of the ballads (Stay With Me, a beautiful song which somehow

I still have not managed to release), and did a time calculation.

One thing I had decided early on was that if I was going to put out an

album of any kind, it was going to be of good listening length, which

to me was between 45-60 minutes. With the new song lineup, texas

was pushing it at 55 minutes, and I felt I would rather err on the side

of leaving the listener wanting more rather than wishing there were less.

A flow became clear, and I accessed a few of my more experimental recordings

to link the songs up, painting a backdrop through which all of these tales

could travel.

It was at this point that I got a little fearful. I knew how I wanted

the thing to go, but I had no idea of the mechanics that would make the

record do the transitions that I was hearing. I hit the bulletin boards,

and found that much of what I needed would have to be done by the mastering

engineer. Which of course I didn’t have yet.

Once again I will point out how this record is a document of a period

in time. Every choice I had made, from the band breakup to the home recording

to the NYC move to finding Paul, had been made possible because of new

technology. I only got regular access to the internet in the spring of

1999, and by the end of that year, my life was totally shaken up.

Again in 2003, the internet came to rescue me. I sifted through a few

mastering engineers I bumped into on boards, and wisely chose Arthur Winer.

He had recently gone solo as well, after a stint with a major Manhattan

studio, and his comfy apartment right by Prospect Park was the perfect

place to think through the segues and make sure the mixes were as good

as they could get.

Knowing now how primitive the source material I gave him was, it’s

nothing short of a miracle how he made it sound like something you might

want to listen to. My hat remains off to him.

There was of course the little matter of paying for all this. By 2003,

my wife had a permanent job, but we were still coping with New York prices,

and with my temp income, we were just scraping by. Mastering and pressing

all told were going to cost close to $3,000, a sum that very seldom appears

in my life as one chunk. I am eternally grateful to those who pre-ordered

the disc, having zero idea of what they would be getting in return. Even

with the pre-orders, I did eventually cash in my old 401k to cover the

costs. I’ll leave it to history to decide if that was the right

choice.

So here was this record, buzzing through my ears. But what to call it?

All along, I had planned to title it Me Grimlock, for some reason

or another. However, a temp stint at a trademark registration company

straightened my thoughts on copyright infringement, and swayed me towards

something less litigious.

In keeping with the original title, my ideas for cover art were all dinosaur-based.

However, no one I knew had any suitable photographic skill to make something

eye-catching and thematically sound. With the scrapping of Me Grimlock,

the visual possibilities opened up. I did briefly flirt with an image

by a photographer I met at a temp assignment, but that shot contained

a Darth Vader helmet, so again the spectre of hovering lawyers backed

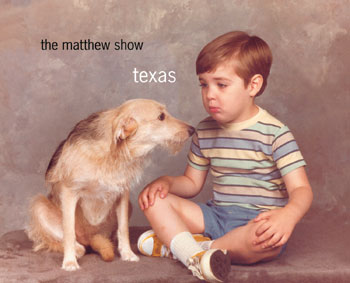

me down. At last, my wife suggested The Picture.

It had sat on my parents’ shelf since the day they’d gotten

it back from Olan Mills. It was a family in-joke, a badge of weirdness

that only we would wear. Look at that photo of me and my old dog Doc,

and you basically know everything you need to about my family. And yet,

I shied away from using it at first. Like the Office Suites,

it seemed gimmicky. Would anyone take songs seriously if they had that

cover attached to them?

But the more people I showed it to, the more I became convinced that its

weirdness was exactly the edge I needed to get anyone to look at me twice.

Indeed, the cover has gotten far more compliments than the record itself

over the years. With that image in mind, and the knowledge that this was

a document of a journey not just to, but from, the name texas

sprang to mind. The lower-case t was intentional, a little provocation

to the scene and state I’d left, presumably for good. And keep in

mind that these were the GWB years, so Texas was in and of itself a loaded

word. I wrote the liner notes (something I had always wanted to do), and

we were off to the presses.

It’s hard to articulate the exact feeling I had while waiting for

the discs to arrive. This was before iTunes, but I had gone ahead and

posted a couple of mp3s online as bait. They were passed around quite

liberally, and I began to develop a hope that perhaps the album’s

release could represent a commercial breakthrough in the new online music

landscape. It was a strange thought, since the whole enterprise had been

undertaken as a withdrawal from the business side of music. I was both

proud and hopeful.

The day the big boxes arrived at my wife’s job, I took off work

early and shot uptown to pick them up. We had moved to a new shoebox in

Hell’s Kitchen by then, and I’m pretty sure I wheeled them

home in our laundry cart rather than take a cab. Upon opening a box and

holding one in my hand for the first time, I was transfixed. There it

was. This thing that came from nothing. And it was good. It wasn’t

perfect. But it was good. And it was itself. It couldn’t be mistaken

for anything else.

I probably stared at that first copy for a good half-hour, taking it all

in. Then Mr. Productivity kicked in, and I began stuffing envelopes. The

pre-orderers got the first round, as was their right, followed swiftly

by the guest musicians. I sent a few out to local clubs, and managed to

get a gig at Galapagos in Brooklyn, one of my favorite places, not to

mention a spot at the Wreck Room in Fort Worth during a visit home.

It is here that I must admit some unintentional self-sabotage. In thinking

of this album, and indeed of the matthew show, as an anti-establishment

enterprise, I sought to throw all the babies out with all the bathwater.

I had seen enough of dudes on stools with acoustic guitars, and was not

enamored of presenting myself as a singer-songwriter, which were a dime

a dozen. I wanted my performances to truly be shows.

What I didn’t realize was that I was not capable of putting on the

sort of show I wanted, and that my compromises on this front were not

sufficient. I cobbled together a sound & light rig, and developed

a poorly-wrought onstage persona. Anyone who saw my gigs during late 2003

and early 2004 saw something that fell short of the promise that texas

showed, and I fear I lost some people then. Maybe a lot. I’ll never

really know.

However, outside of the live performance realm, I did fairly well. For

13 months solid, I stuffed envelopes with discs and mailed them to every

blogger, music reviewer, indie filmmaker, and radio station that I possibly

could. My postal receipts were copious, and dwarfed any profits made from

sales. But I sensed that this was my chance to break into a higher stratum

than I had previously occupied, and I chased the nameless prize with religious

fervor.

I got written up a LOT. Look up most of my reviews on the website; the

bulk of them are for texas. But of course very few of the outfits

that gave me press are still in existence. Most faded within months. As

I neared my 13th month of solid promotion, it became clear that the breakthrough

I had allowed myself to hope for would not materialize, at least not with

this record.

It surprised me. Not just the absence of a break, but the fact that I

had once again gotten myself in a mindset that placed commerce over art.

I had barely touched the studio since the album’s release, and my

creative energies were restless. I remember well the day in late 2004

when I decided that the time had come to end texas’ status

as a new album, and to begin work on fresh material. From my hovel in

New York, it felt a little like defeat.

Fans of february won’t be surprised that the experience

of making and promoting texas weighed heavily on my sophomore

production. That second album was originally going to be titled The

Disappointment Project; not exactly a moniker built for making a

sale. My thoughts on that record will wait until its 10th anniversary

in 2018, but I will say that it and texas are inextricably intertwined.

But here’s what I didn’t know.

Like seeds on the wind, fans of texas were sharing it with friends.

Copies were finding their way into people’s hands at used record

stores (largely courtesy of The Picture, I suspect). Files were shared

far and wide. It turned out that texas was building a reputation,

one that wouldn’t become clear to me for many more years.

I bought a new studio rig. We had a baby. NYC was a great experience,

but in the absence of any real prospect for financial success, it was

a tough place to live. In January of 2006 we returned to Texas, and I

began reconnecting with some of my musical roots.

A funny thing happened then. In places where I’d never been, people

knew who I was. This still happens today, and more often than not it is

linked with them having heard texas at some point. It’s

a little inexplicable. I do not consider it the finest musical work I’ve

created, although there are some gems in there. Obviously being present

at its creation, I hear all the missteps and paths not taken, which other

ears would never guess at.

But listening back to it now, 10 years after it went public, there is

something peculiar about that record that still draws me in. And it’s

not just me. Office Suite, Part I remains my top-selling song,

due partially to its regular inclusion in viral YouTube videos and podcasts.

The tune I nearly chopped, now paying my bills. I recorded that track

in only 3 hours, leaving all the mistakes on tape, figuring it was a throwaway.

Maybe there’s a lesson in there somewhere.

Could I ever make texas again? Of course not. The person who

made that record was changed by it, and by everything that’s happened

since then. I continue to push my boundaries, and remain intrigued by

trying things I haven’t done yet, which of course means that all

my tricks on texas are stale to me. But that album remains a

document of a time when those ideas were fresh, and were pursued with

no thought as to their consequences. I like that, and I can hear it in

every track. It is truly a snapshot of a place to which I will never return,

and I’m damned glad I made it, if only to remind me that such places

exist, so long as we take the time to seek them out. If we are not afraid.

If, to paraphrase Mr. Melody, we simply make a record we like.

I have done that, and if you’ve read this far, I thank you for taking

the time to listen to something you knew nothing about, and to find beauty

in it. That is the gift that was given to me by putting texas

out into the world for you to discover. I’m happy that you joined

me in that journey, and I hope that we will continue to find more unexplored

territory together.

Onward.

(material from the texas bonus disc follows, for those who may be curious...)

Fat Old Sun - Written by David Gilmour, performed here by me and Nancy Giammarco

The Wandering Jew, Part I - An instrumental that eventually found its way onto a season of Roadtrip Nation

The Wandering Jew, Part II - Likewise.

The Death of Ennui - I wrote this shortly after September 11, 2001. It's hard to say whether it's technically about that day, but it definitely arose from the mood in which I found myself.

The Loneliest Boy In Toyland (original demo ending) - I made this for Paul so he could get a feel for it. For the demo, I played a suitcase with a pair of drumsticks and put some distortion on it. Listen for the elves at the end. I don't know what's the matter with me.

Bring Me Safely Down (original version) - I was going to use this version for the album until it got completely erased, per above. The horror. Though I mostly prefer the re-do on the album, this one has a certain character. The audio is taken from the only surviving cassette copy of the rough mix.